|

In my Pranayama (breath and energy control) practice this morning, I noticed my autonomic nervous system. I bumped up against it several times as I tried to inhale or exhale while it didn't think I needed to.

The friction happens most notably at the end of the exhale. The lungs are empty and the most "natural" thing to do is inhale to fill the lungs. The autonomic nervous system tells us "breathe in." So we usually do. During Pranayama practice, as I hold my lungs empty or inhale very slowly, the friction with my autonomic nervous system is palpable. It wants me to inhale quickly, but I consciously inhale slowly or not at all. The second place where friction happens is when my blood has enough oxygen. In this state, my autonomic nervous system says, "No need to breathe so much. Either exhale or be still." During Pranayama practice I am sometimes in this physiological state only midway through the inhale and I try to complete the inhale. It is very difficult, like my muscles and brain shut down, preventing me from inhaling further. I have yet to navigate this obstacle, but I predict that at some point my autonomic nervous system will settle and I will be able to inhale at will. When I arrive to this level of control, I will need to be incredibly careful about the state of my physiology, my heart rate and blood oxygen content because I will be consciously overriding an autonomic function designed to keep my body and brain supplied with the correct amount of oxygen. The amazing thing about controlling the breath over several minutes is the realization that breathing is usually so subconscious. Even if we control the breath for a moment, we soon release it and let the autonomic nervous system monitor and govern it. We never get too far from the self-regulated balance of oxygen in the blood. I think I may be approaching the true power of Pranayama practice: the awareness and even control of the autonomic nervous system. It is both exciting and frightening. I have to be very careful.

0 Comments

There are a few movements that we can not or do not do in most yoga practices. Pushups and pull-ups are among them. These two exercises strengthen some major muscles of the body that are otherwise neglected by yoga postures.

PUSHUPS "What about Chaturanga?" you may ask? Chaturanga is a pushup-like motion that is intentionally done with the arms close to the body. The hands are low and the elbows close to the torso. This is done to prepare us for Upward Facing Dog posture, where we straighten the arms to bend the spine backward and stretch the chest, belly and hips. Chaturanga is great for setting up Upward Facing Dog, but it is hard on the arms and elbows. It purposely bypasses the chest muscles so that we may bend the spine backward in Upward Facing Dog. The triceps and elbows are not designed to move the weight of the body, especially not repetitively. The chest muscles, on the other hand, are large and powerful, made for moving large loads. We can strengthen the chest muscles by doing pushups, with the elbows widened away from the torso, the hands a little wider than the shoulders. PULL-UPS Two other important muscles that get neglected in most yoga postures are the biceps and the latissimus dorsi. The biceps are the muscles that bend the arms at the elbows, so it is difficult to use body weight to develop them. (Far easier is to develop the triceps that straighten the arms. These are activated every time we use the arms to hold our body weight off the floor.) Pull-ups strengthen the biceps, lifting the body weight by bending the arms. The latissimus dorsi are huge muscles that attach our arms to the lower back. It is thought that this is useful for hanging and swinging, a remnant of our descending from apes. The "lats" are powerful muscles that get very little exercise unless we hang from our arms. Pull-ups are great for that. I like to approach the physical body with some logic and science. I've never been one to practice yoga as-is just because of 'tradition'. Pushups and pull-ups are two non-yoga exercises that allow us to develop large, important muscle groups that are otherwise neglected. This leads to even development of the body. The first set of postures in Bikram's class is the Half Moon series, where we bend the upper body to both sides and then backward. These positions warm the body effectively because they stretch the same muscles that are engaged and strengthening. This generates a lot of heat.

When we bend to the right side, we are held up by the muscles on the left side of the body - in the hip, abdomen and torso. These are the same muscles that are being lengthened, so the body and mind must find a balance between engagement and release. Technically speaking, this is called eccentric contraction -when a muscle is engaged while getting longer. Contrast this with concentric contraction, where we engage a muscle and make it shorter, like a bicep curl or Cobra Pose. In concentric contraction, the muscles opposite the contracting muscle automatically relax and lengthen. In a bicep curl, the triceps relax. In Cobra Pose, the front chest, abdomen and hip flexors relax. The fourth posture of the Half Moon series is Hands to Feet Pose. Unlike the side and back bends, Hands to Feet Pose is not an eccentric contraction. We contract the abdomen in order to stretch the back, so it is concentric contraction. This series of warm-up bends would be better served by an eccentric forward bend that engages the backside of the body while stretching it. This is quoted from Gregor Maehle's site Chintamani Yoga. A great site.

"There is a widespread misconception that postures should be painful. As a rule of thumb, postures should not be painful, which is something that even the ancient masters pointed out. Patanjali states in Yoga Sutra, “heyam duhkham anagatam,” which means that new suffering needs to be avoided (Yoga Sutra II.16). The reasoning behind this injunction is simple. Every experience you have forms a subconscious imprint (samskara). Every subconscious imprint, whatever its content, calls for its own repetition." "Practitioners should analyze the postures and continually correct their performance of them until awareness is spread all over the body. When that happens, the body is hardly felt anymore. This sounds paradoxical, but you feel the body mainly when something is wrong. The absence of negative feedback means that everything is okay. When the body is correctly aligned, a feeling of stillness and firmness yet vibrant lightness arises. The mind becomes luminous, still, and free from ambition and egoic tendencies. This is the state that you are looking for. It is conducive to meditation. When this quality is achieved in a posture, that posture is fit as a platform for the higher limbs of yoga." Read the whole article here.  While practicing this morning, I noticed something interesting and powerful while standing with my feet together and arms extended overhead (pictured). When I found my center of gravity - the point of balance where my weight is shifted neither forward, backward or to the side - my body automatically engaged in so many of the ways they harp on in yoga class. My weight is in my heels with only slight balancing weight in the big toes and small toes. My quadriceps engage, though only slightly. They are certainly not limp, but they are also not tight and locked with great effort. The slight engagement of my quads lifts my kneecaps. My pelvic floor (mula bandha) and lower belly (some call it uddiyana bandha) engaged, though again not intensely; about 50% of a mind-driven muscle engagement. My point of focus was my spine and keeping its natural curvature. When my spine is relaxed and strong and my weight is centered in opposition to gravity, the body seems to spring upward and open. It floats without effort but remains absolutely present. This makes me re-think the way that we teach muscle engagement in yoga class. For years I have heard: "Lock the knee, lift the kneecaps, engage Mula Bandha!" as if they are independent mental engagements like puzzle pieces that make a proper posture. But more and more it seems that these are results of a proper posture instead of the building blocks. If someone wants to be a race car driver, they don't begin by driving at 150mph even though that is the most obvious characteristic of a race car driver. They begin by learning to drive with perfect awareness and the speed will come. The same seems true of yoga postures and specifically these physical engagements. The engaged quadricep, lifted kneecap and Mula Bandha are results of proper balance in the body. Perhaps we should be teaching balance and body awareness in space instead of which muscles to engage. After all, our muscles are designed to serve the body, not the body to serve the muscles. ps. This posture (standing or sitting with arms extended overhead) reminds me also of ancient yogic postures designed to awaken the body's energy. It could be that this is a fundamental and powerful position for the body. We all know that we should drink plenty of water to stay hydrated. Did you know that water molecules - H2O - are necessary to break down our food and nutrition? Without sufficient H2O we can't break the food we eat into smaller sugars that our body uses for energy. Even if we eat the best and healthiest foods but not enough H2O, we can't digest them effectively.

So be sure to drink plenty of water. Your body needs it to function and especially to get the most out of the food you eat. A post from my teacher Tony Sanchez.

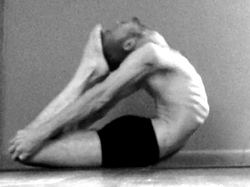

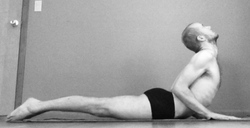

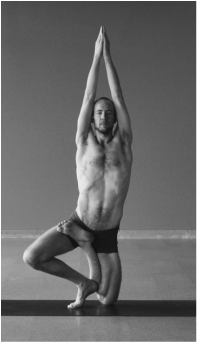

YOGA METHODS When yoga teachers and students stop learning and develop bad habits [they] perpetuate ignorance in the practice of yoga. To change and improve established systems is part of our journey. We must rely on scientific knowledge to develop the best yoga practice possible. Many times old unproven yoga methods lead to disaster. We have the power and the access to new more powerful ways to take yoga into the future. Study, practice and research ways to improve your own yoga practice. Use scientific principles available to unfold the beauty and power of yoga. At the beginning of your yoga path, it is important to find a knowledgeable yoga teacher with no ulterior motives. Once your foundation is formed you are on your own.  Full Cobra 4 Full Cobra 4 Today my Cobra practice reached a new level of focus and openness. I was able to hold onto my knees while putting my feet on my head. I have been practicing toward this variation for a few months now, but I have not had the combination of openness in my chest and upper back and strength in my back, legs and buttocks.  Cobra Cobra For 3 years I practiced only the regular Cobra, where the yogi builds back strength and spinal flexibility by lifting the shoulders and chest off the ground. This posture is one of the foundations of a yoga practice. I still practice it regularly.  Full Cobra 1 Full Cobra 1 When my strength and flexibility reached a good level about a year ago, I began to deepen the bend in my spine. This is the first of what I consider to be the Full Cobra backbends (I call this Full Cobra 1), where the yogi bends the spine as deeply as possible including the neck. It is different from the regular Cobra (above) in that significant arm strength is used here to bend backward deeply.  Full Cobra 2 Full Cobra 2 Full Cobra 2 achieves the opposite of Full Cobra 1 (above). While Full Cobra 1 uses arm strength to bend the back, Full Cobra 2 (sometimes we call it Flying Cobra) removes the arms and relies only on back strength. I still bend as deeply and completely as possible, but this posture creates incredible engagement in the whole spine and buttocks. It is intense and powerful and builds great strength.  Full Cobra 3 Full Cobra 3 To complete the body's energetic circuit and put the bottom of the feet to the top of the head, Full Cobra 3 (left) combines a bit of arm strength with bent knees. It stretches the entire front side of the body from the chin to the toes. I will continue to practice all of these variations because each offers something different. As a group they strengthen the muscles of the back, improving posture. They compress the disks of the spine from behind, reducing the risk of herniated disks into the spinal column. They stretch the front side of the body, increasing emotional strength and courage. They stretch the abdomen, increasing intestinal movement and improving digestion and elimination. And they compress the adrenal glands, reducing stress.

If this is not the most valuable group of Postures, it is certainly one of them.

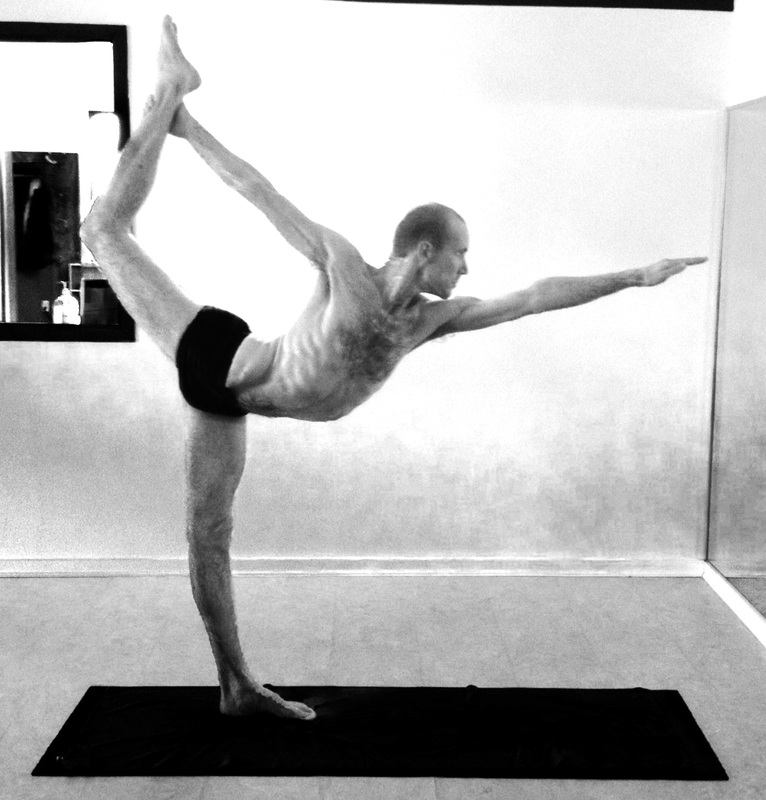

Quite simply, Asana practice is defined by alignment. Alignment is what makes one posture different from another. It is the rotation in the hip that separates Warrior 3 from Balancing Half Moon. It is the bent knee that separates a High Lunge from a Low Lunge. It is the straight arms that separate Up Dog from Cobra. Alignment is simply the position in which we put our bodies. We are always aligned in one way or another. From there it is just a matter of degree: how much attention we pay to the integrity and proper use of our bodies' structures, or how little.

It is understandable and justifiable to see the postures in broad strokes and shapes; to think that as long as we put the big pieces in place we are doing the postures. To a certain extent that is true. But that approach neglects a deep and profound well of strength, flexibility, balance, resilience, patience, compassion, intelligence, focus and calm that awaits us when we explore our bodies and the body-mind connection with more curiosity, depth and attention to detail. The Devil's In the Details Our bodies are tremendous creations, complex and multi-faceted. Which means that it is easy to become overwhelmed by the details and minutiae, especially if we aren't anatomy or bio-mechanics experts. This is true of teachers as well as students. When we feel overwhelmed by the sheer possibilities for our body's alignment, it is normal for us to retreat from it. But, even though alignment can be detailed, it shouldn't be overwhelming. In fact, it should be quite simple. Go Simply I encourage you not to retreat from detailed alignment in your yoga posture practice. Just simplify. When I am frustrated by a posture, I go back to the beginning and find its essence. What is the One thing this posture is trying to achieve? Is it a bend in the spine? Is it a stretch of the hamstrings? Is it strength in the shoulders? Once you identify the most important element in the posture, practice that posture with your mind completely focused on that element. Don't think about anything else. Do that one thing with 100% intention and try to do it perfectly, no matter how good or bad it looks from the outside. After awhile of practicing with complete commitment to the primary intention of the posture, the rest of the posture slowly begins to reveal itself. The body starts to unfold naturally, and you will end up solidly in a posture that you now know intimately and love deeply. And one that is properly aligned. Stay Focused On the Center There is always the availability of countless details about the alignment of the edges of the postures. Consider them for a moment or two, then return your focus to the core intention of the posture. As my teacher Tony Sanchez said during a breathing exercise, "It is a breathing exercise. Focus on your lungs, not your legs." This will keep your mind focused and your postures true. It will bring greater detail and energy to your practice. |

This journal honors my ongoing experience with the practice, study and teaching of yoga.

My FavoritesPopular Posts1) Sridaiva Yoga: Good Intention But Imbalanced

2) Understanding Chair Posture 2) Why I Don't Use Sanskrit or Say Namaste 3) The Meaningless Drudgery of Physical Yoga 5) Beyond Bikram: Why This Is a Great Time For Ghosh Yoga Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed