|

The Ghosh lineage has a tradition of a system of 84 asanas (postures). Both Bose’s (1938) and Mukerji’s (1963) books contain 84 postures. Bikram Choudhury’s “Advanced Class” is sometimes referred to as the “84 Asanas” even though it is more than 84 postures (it comes from a list of 91). Tony Sanchez teaches a sequence of approximately 104 postures but often refers to the 84 postures in the tradition.

84 is a sacred number in many spiritual traditions, representing a harmonious relationship between the individual and the universe. This harmonious relationship is also fundamental to the practice of yoga, so it is no wonder that yogis incorporate the number into their systems. The idea of 84 asanas is an ancient one, though most traditions actually teach more than that. The Goraksasataka, a text from around the 13th century, states that there are as many Asanas as there are species of creatures, that Shiva has enumerated 84 asanas, and that out of all the asanas, only two are particularly distinguished. (GS 5-7) It goes on to describe Siddhasana and Kamalasana (another name for Padmasana or Lotus posture). The Shiva Samhita, from about the 15th century, says that “there are eighty-four asanas of various kinds which I have taught. Out of these I shall take four and describe them.” (SS 3:96) The Hatha Pradipika, popularly known as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, from about the 15th century, agrees with the Shiva Samhita. It says “Eighty-four asanas were taught by Shiva. Out of those I shall now describe the four important ones.” (1:33) The Gheranda Samhita, from about the 17th century, says, “All together there are as many asanas as there are species of living beings. Shiva has taught 8,400,000. Of these, eighty-four are preeminent, of which thirty-two are useful in the world of mortals.” (2:1-2) The text goes on to describe those 32 asanas, by far the most in any old yoga text. As history has progressed and the practices of yoga have gotten more physical, the number of asanas that are actually instructed and practiced has increased. Today there are hundreds of asanas practiced in any given tradition, including Ghosh. But the symbolic power of the number 84 stays the same. In short, the idea of 84 asanas is a historic, sacred and symbolic one, not necessarily a practical representation of a tradition of actually 84 postures. Excerpted from the upcoming Ghosh Yoga Practice Manual, Advanced 1

0 Comments

We are two weeks away from the first ever Ghosh Yoga Practice Week. Ida and I are passionate about creating an environment where yogis can delve deeply into their own practices and learn more progressive techniques and ideas.

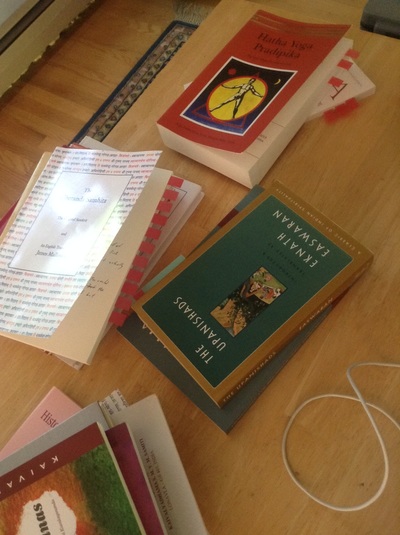

As we finalize the schedule and the topics to be covered, I am neck-deep in books. And I love it. It is a challenge to balance the history and academic side of the tradition, the modern propensity toward athletic asana, anatomy and physiology, and our own personal experiences. But balance them we shall! I am especially excited about the morning practice sessions, which will combine therapeutic exercises that we learned in Kolkata with beginning and intermediate asana. One thing I've always loved about yoga is how the same posture can have several different names, depending on the lineage and historical period. Or the same name can refer to any number of different positions. Learning all the names and positions is something that floats my boat. It's like yoga trivia mixed with history and tradition. I find it funny and interesting, and at the end of the day it tells me that the names are only as good as their ability to transmit the idea of a posture to another person. (Though there is the school of thought that, once you know the true name of something, you understand it completely.)

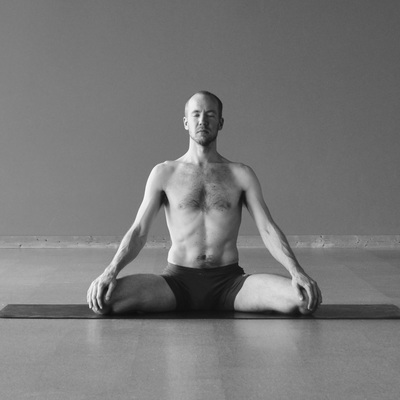

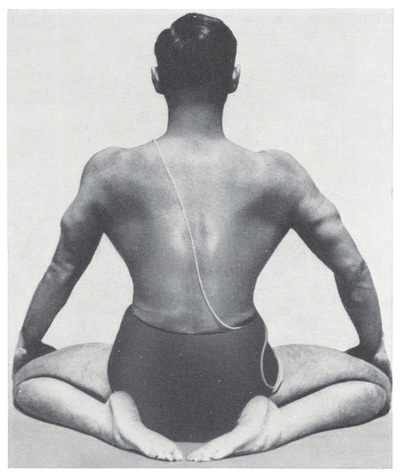

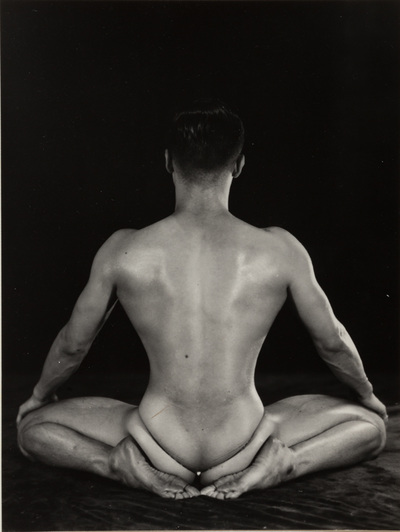

A posture that has been lost to the Ghosh Lineage for some time is Mandukasana, Frog Posture. If you are familiar with other traditions, there are several postures that bear the name "Frog." Even Tony Sanchez uses the name "Frog" for a different stretching posture in his intermediate series. Bikram doesn't include Frog Posture in his "complete" list of postures, and so it has disappeared from a whole generation of his disciples. I was first introduced to it while editing Buddha Bose's book from the 1930s. It also appears in Gouri Shankar Mukherji's book from the 1960s. Also, there is a photo on the wall of Ghosh's Yoga College in Kolkata that shows Dibya Sundar Das in the posture. I began practicing it out of curiosity. It is intense at first, in both the knees and the hips. But once I settle, it is quite stable and strong. It is wonderful to prepare the lower limbs for Lotus, something that I care more and more about every day. Ida and I have begun taking photos for the first of our Advanced Practice Manuals, and we are including Frog Posture. Since both Bose and Mukherji's photos of the posture are from the back, to show the detail of the feet, it was almost surprising to see it from the front. Above I am including a picture of the front of Frog Posture. I'm also including my picture of the back just for fun. You will notice how similar it is to Bose's and Mukherji's. As we put together the first of our Advanced Practice Manuals, Ida and I have been discussing yoga at length. Even more than usual. It distresses us that there is a scarcity of intermediate and advanced instruction. Is there a scarcity of advanced yogis? Do they keep their knowledge secret? Is advanced knowledge weeded out by supply and demand, unable to compete with the plentiful demand of curious beginners?

What postures and practices should a progressing yogi do? When and how often? Why, and are there any that are pointless, precarious or dangerous? What role do foundational practices play as we advance? What is yoga's purpose in light of our changing culture and growing physiological knowledge? What impact does asana have on the mind and the spirit? And, perhaps most importantly, where does the practice of yoga take us and what is the role of asana on that journey? We have been living these questions. We put them in our minds, our bodies and our breaths. We have discovered the answers to some of them, but others seem elusive, bringing only more questions. Some answers are in ancient philosophical texts, some in modern medical studies, and some have never been written down. As I write this, I am struck by how much we are defined by the questions we ask, even more than the answers we have. Our questions determine our direction. They define the scope of our imagination and our potential. They point to where we will be in the future. As I study old yoga texts, I am struck by the numerous teachings of philosophy and mental control amidst a near-complete lack of references to the physical body. Yoga took a turn for the physical about 500 years ago with the Hathapradipika which describes the forceful physical practices of Hatha Yoga. But even it describes all of its practices as preparation for the Concentration, Meditation and Contemplation of Raja Yoga.

As a child of the 20th century, I first learned yoga as a physical practice. One that heals the body and unifies the body, breath and mind. The more I learn about yoga tradition and history, I realize that the current iteration of yoga as mindful exercise is a recent development, about 100 years old. It continues its shift toward physical fitness, becoming more athletic and less mental with each passing day. I wonder how we came to this place. How did yoga, a philosophical and mental discipline, turn into a practice of sweating, backbending, handstanding and physical health? I came across a revealing tidbit this morning: "Whereas Vivekananda and Aurobindo [circa 1900] addressed the intellectuals and propagated a spiritual and metaphysical yoga, Kuvalyananda and Yogendra made it available to the 'man in the world', and sought to use it for health improvement. 'Yogendra and Kuvalyananda transformed the practice of yoga into a physiologically based form of physical education and attempted to turn it into a scientifically verifiable form of therapy.' This change in orientation is...the defining moment in the emergence of modern yoga. For the first time, the physical, worldly and health-promoting aspects of yoga were given priority over the mental, spiritual and liberation-promoting ones. The proliferation of modern forms of yoga, many developed by Westerners, can be seen to be rooted in this fundamental shift. Moreover, it would be fair to say that in the West and, indeed, in much of modern India, a yoga class is generally understood to be concerned with physical movement, stretching and breathing first and with meditation, philosophy and spirituality only second." -from A Student's Guide to the History and Philosophy of Yoga, by Peter Connolly Lately I have become occupied with the concept of Pratyahara or withdrawal of sensory focus. It is the 5th limb of yoga according to Patanjali. He gives it its own limb, yet I rarely hear anyone speak of it or teach it. Whenever I ask fellow yogis about it, they often say something to the effect of "turn your attention inward." This is not enough for me.

Near the end of the Katha Upanishad is the first clear definition of yoga that we have. It describes yoga as the stilling of the senses. The chariot metaphor we have all come to quote so often - that equates yoga with reigning in the horses that are drawn toward environmental stimuli - is a description of sensory control (the horses are our senses). The first several historical instances I have studied, including the Katha Upanishad, the Yoga Vasishta and even the Bhagavad Gita, define yoga as the control of the senses to still the mind. These predate Patanjali's Yogasutras, where he includes 3 higher limbs. Right now I am toiling under the belief that Pratyahara is the first element of the union that is yoga. I don't doubt that there are higher states to pursue, but for now I am researching, studying and practicing sensory control. ps. As I understand it, food is a sensory object. A yogi must control his cravings for food the same way he controls his cravings for visual distraction. The Yoga Yajnavalkya states that "A monk may have eight mouthfuls of food daily; those in retirement, sixteen mouthfuls; a householder, thirty two; and students as much as they wish."

The other day I ate at Qdoba. I got a bowl with rice, beans, lettuce, tomatoes and cheese. I counted my mouthfuls as I ate. After 20 mouthfuls I lost interest in eating any more. I had eaten about half of the bowl. Have you ever counted your mouthfuls? I have become acutely aware of my relationship to food. I often put edible things in my mouth out of boredom or tiredness. It distracts my mind and brings all my attention to my senses and my belly. I am comforted. As I read more old yoga texts I am struck by how often they refer to restraint and austerity as vital to the path. Some even say that restraining food intake is of the highest importance. They are of course not talking about yoga in the modern, western, health and fitness way, but in a mental and spiritual way. Regardless, it is illuminating to note how powerful is the attachment to food, eating and the sensations of eating. If we aspire to things like mastery over the senses (Pratyahara), we must come face to face with our attachment to food. I have been asked several times in the past few months why I don't say Namaste at the end of class and also why I don't use Sanskrit terms or names for postures. The answer is, mostly, clarity.

SANSKRIT I don't speak Sanskrit, and none of the students that I've come across speak Sanskrit either. Most of us in the US speak English, so it feels natural to me to speak English when I teach. There is somewhat of a tradition in yoga to use the Sanskrit names of postures. At its best, it offers a sacredness and gravity to the practice, at its worst it creates elitism and confusion. I have never been one for following traditions out of deference. I prefer to test each lesson and practice in the context of modern civilization and my own life. I find that yoga is easier to understand, practice and teach when I use common language. It allows me to relate to the practices instead of revere them, and as a teacher I encourage my students to do the same. We practice yoga because it benefits us, not because it is traditional. NAMASTE Namaste (literally translated as "I bow to you") is a respectful greeting that can be interpreted as anything from "salutations" to recognition of the divine in another person. It is a Sanskrit word, and my dislike for its confusion is the same as above. But the cultural and spiritual implications of the word also trouble me and keep me from using it. I am not Hindu. The meaning that we give namaste in yoga is a distinctly Hindu one, something along the lines of "I bow to the divine in you" or "I see the same divine light in you as I see in myself." While I think these are beautiful and powerful phrases, they assume a certain level of Hinduism that I don't take lightly. THE DIVINE The path of yoga gradually reveals to us the underlying nature of reality, in which the "Divine" is universally present in all people, beings and things. But even that explanation takes on Hindu terminology and a Hindu relationship to God. Personally, I have not progressed far enough on the path of yoga to make this statement unequivocally and with integrity. I can understand it in theory, but that is a far cry from the first-hand experience and understanding I prefer before adopting language and teaching into my life. RESPECT The idea behind Namaste is a beautiful one, at least the way it has been generally appropriated in western yoga. A recognition of effort and goodness in others. I prefer to say these things clearly, concisely and in my own language. I gladly offer respect, gratitude, honor and joy when I feel them. I simply use those words. I just finished reading Gregor Maehle's new book Samadhi. In it he describes the eighth and final limb of Ashtanga Yoga.

It is becoming clearer to me that asana (postures) are a small part of yoga. They are certainly not its goal. They serve the vital purposes of bringing health to the body, allowing us to sit for long periods of time in stillness, and strengthening the body to tolerate the intense energetic effects of Kundalini meditation and samadhi. Yoga directs us toward understanding the nature of the mind and of consciousness. The 8 samadhis allow us to experience them firsthand instead of simply thinking about them theoretically. As a yoga teacher in the USA, my teachings are focused around asana. I think this needs to change. Today we use the time in-between classes to wander through Calcutta. We start at a coffee shop in the book district. The coffee is not very good, but it is nice to sit, drink and converse. Our wanderings take us around old Calcutta, and we end up at the Vivekananda museum, the huge property where he grew up that was eventually separated and then restored to its former and present form.

I like Vivekananda, but mostly the visit reminds me of my desire to learn more about Ramakrishna, the Hindu priest who knew God through many Hindu deities as well as Islam and Christianity. “I have found that it is the same God toward whom all are directing their steps”, he said. |

This journal honors my ongoing experience with the practice, study and teaching of yoga.

My FavoritesPopular Posts1) Sridaiva Yoga: Good Intention But Imbalanced

2) Understanding Chair Posture 2) Why I Don't Use Sanskrit or Say Namaste 3) The Meaningless Drudgery of Physical Yoga 5) Beyond Bikram: Why This Is a Great Time For Ghosh Yoga Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed