|

I feel a great sense of relief.

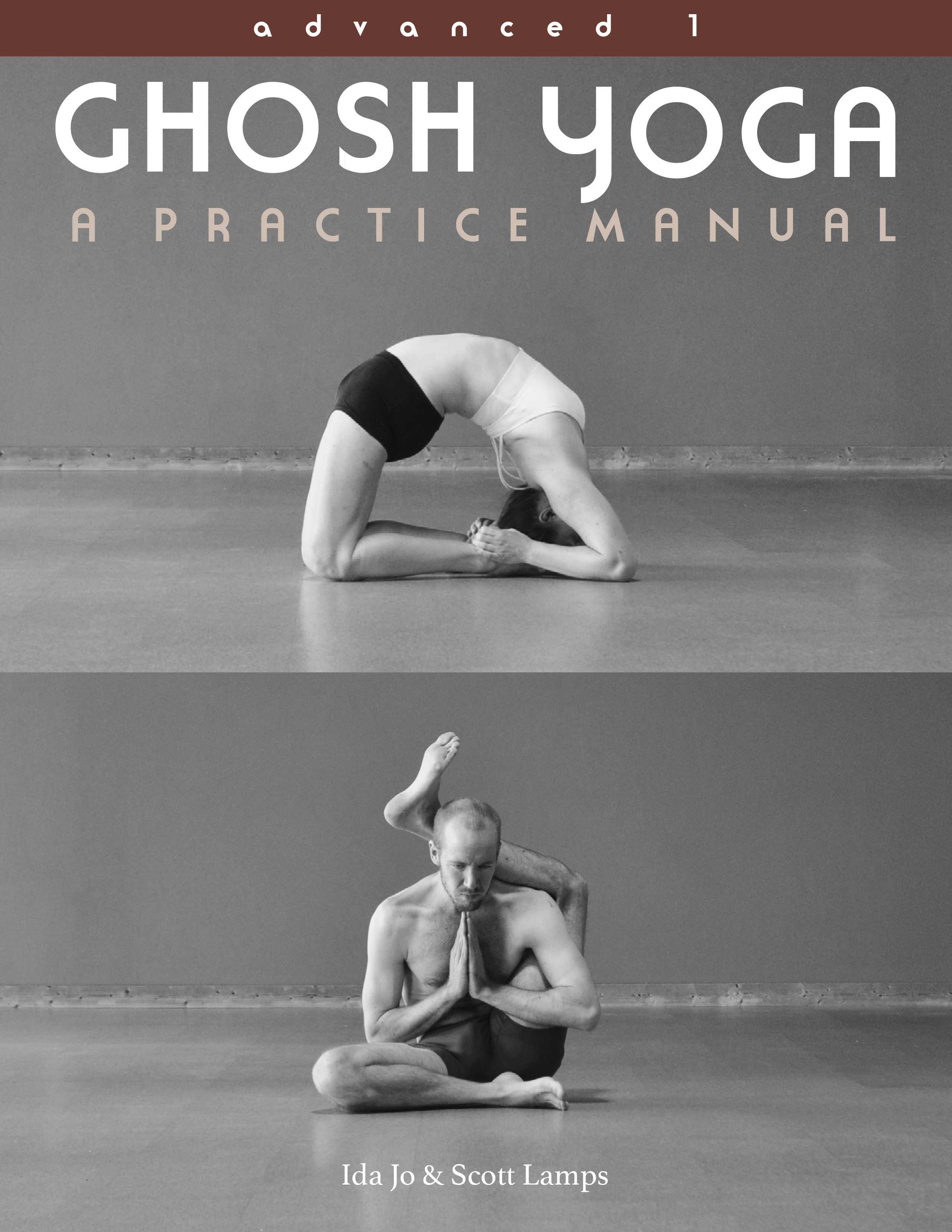

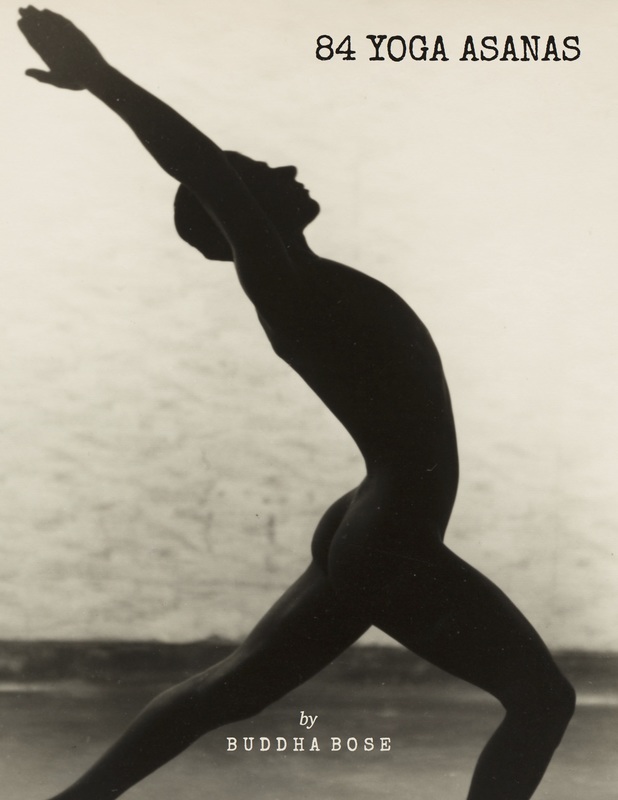

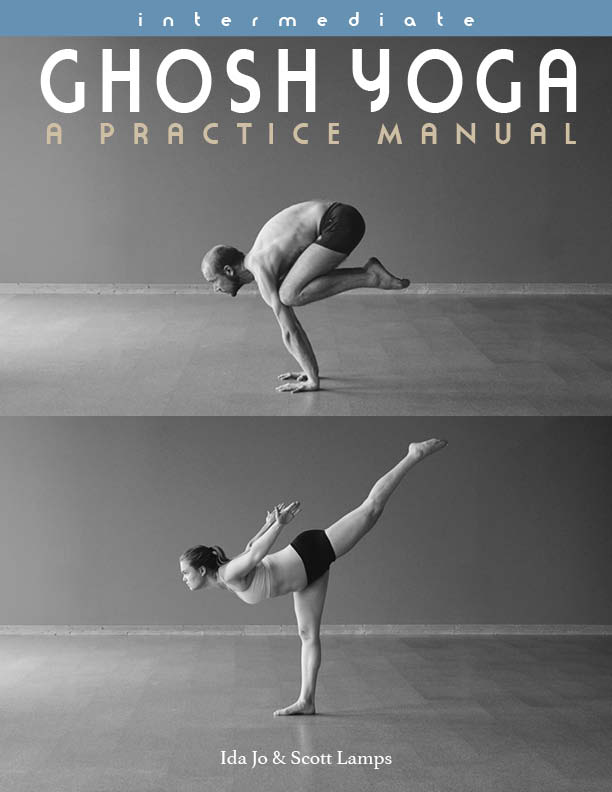

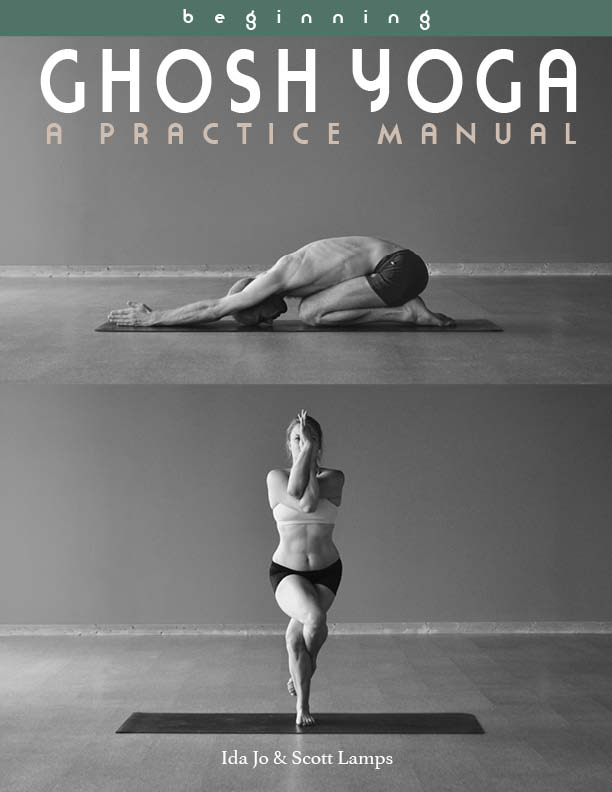

This is the final proof of the upcoming Advanced Practice Manual. Just about every ounce of my creative energy for the past 6 months has gone into this book. The words, the pictures, the explanations, the research. As we near completion, I realize how all-encompassing the project has been. This book builds on the Beginning and Intermediate Practice Manuals that we published last year. It has 56 postures and preparations, 8 breath control practices, 6 sensory control practices and 15 sequences for general and specific practice. At 295 pages, it is more vast than either of the previous two. Ida always says it makes sense that an advanced volume would be more detailed and therefore bigger, but I always imagined the advanced instruction would get simpler. I was wrong. As the practices get more advanced, the need for detail grows almost exponentially. While a beginning practice can bring benefit to pretty much anyone, advanced practices get subtler. We walk on the razor's edge, where small adjustments can mean the difference between benefit and detriment. "Advanced 1" will go to the printer in a week, and we'll ship the first pre-orders in early January.

3 Comments

We are two weeks away from the first ever Ghosh Yoga Practice Week. Ida and I are passionate about creating an environment where yogis can delve deeply into their own practices and learn more progressive techniques and ideas.

As we finalize the schedule and the topics to be covered, I am neck-deep in books. And I love it. It is a challenge to balance the history and academic side of the tradition, the modern propensity toward athletic asana, anatomy and physiology, and our own personal experiences. But balance them we shall! I am especially excited about the morning practice sessions, which will combine therapeutic exercises that we learned in Kolkata with beginning and intermediate asana. I have never been a person who adheres to traditions naturally. It always made more sense to make my own way, to take one teaching from here and another from there, mash them together and develop my own viewpoint. I suppose I've been sort of a rebel, but in the least cool kind of way. More like an outcast who doesn't really fit in anywhere.

Lately my yoga teaching has uncovered a new aspect of my personality. I find myself subordinating my own intentions or personality and putting myself in service of the practices of yoga. These are practices, physical and mental, that I know from experience to be quite powerful and transformative. I know that if others simply do the practices - though admittedly it is not so simple - they will undergo the same transformations that I have experienced. And so it is not my instruction or the power of my radiant personality that might make me an effective teacher. It is the degree to which I can get the students to do the practices with integrity. No more and no less. A personal story might lift the mood of a class, but it doesn't necessarily improve the students' relationships with the practices. And it is the practices that transform us, not the personality or brilliance of a teacher. (You may have read about what happens when students follow a teacher instead of the practices. Cult-like communities form that almost always lead to abuse, corruption and lawsuits.) I have never been in this position before, realizing that my viewpoint is not important except in the way that it can clearly communicate these practices of body, breath and mind. The true power is in the practices themselves. Now I sound like a traditionalist, encouraging adherence to the "proper way of doing things." It is not that these practices work because they are traditional. They have become traditional because they work. As we put together the first of our Advanced Practice Manuals, Ida and I have been discussing yoga at length. Even more than usual. It distresses us that there is a scarcity of intermediate and advanced instruction. Is there a scarcity of advanced yogis? Do they keep their knowledge secret? Is advanced knowledge weeded out by supply and demand, unable to compete with the plentiful demand of curious beginners?

What postures and practices should a progressing yogi do? When and how often? Why, and are there any that are pointless, precarious or dangerous? What role do foundational practices play as we advance? What is yoga's purpose in light of our changing culture and growing physiological knowledge? What impact does asana have on the mind and the spirit? And, perhaps most importantly, where does the practice of yoga take us and what is the role of asana on that journey? We have been living these questions. We put them in our minds, our bodies and our breaths. We have discovered the answers to some of them, but others seem elusive, bringing only more questions. Some answers are in ancient philosophical texts, some in modern medical studies, and some have never been written down. As I write this, I am struck by how much we are defined by the questions we ask, even more than the answers we have. Our questions determine our direction. They define the scope of our imagination and our potential. They point to where we will be in the future. I often wonder about the purpose of my life.

How will I know if I am fulfilling my purpose? How will I know if I have a purpose? What might that purpose be? I ask myself a simple question: "What do I think needs to be different?" From there things become simpler and clearer. I take the steps required to bring about change, usually by offering something new or ceasing to do something I have been doing mindlessly. This is a straightforward way to honor ourselves and our unique visions, and to slowly change the world. I have been asked several times in the past few months why I don't say Namaste at the end of class and also why I don't use Sanskrit terms or names for postures. The answer is, mostly, clarity.

SANSKRIT I don't speak Sanskrit, and none of the students that I've come across speak Sanskrit either. Most of us in the US speak English, so it feels natural to me to speak English when I teach. There is somewhat of a tradition in yoga to use the Sanskrit names of postures. At its best, it offers a sacredness and gravity to the practice, at its worst it creates elitism and confusion. I have never been one for following traditions out of deference. I prefer to test each lesson and practice in the context of modern civilization and my own life. I find that yoga is easier to understand, practice and teach when I use common language. It allows me to relate to the practices instead of revere them, and as a teacher I encourage my students to do the same. We practice yoga because it benefits us, not because it is traditional. NAMASTE Namaste (literally translated as "I bow to you") is a respectful greeting that can be interpreted as anything from "salutations" to recognition of the divine in another person. It is a Sanskrit word, and my dislike for its confusion is the same as above. But the cultural and spiritual implications of the word also trouble me and keep me from using it. I am not Hindu. The meaning that we give namaste in yoga is a distinctly Hindu one, something along the lines of "I bow to the divine in you" or "I see the same divine light in you as I see in myself." While I think these are beautiful and powerful phrases, they assume a certain level of Hinduism that I don't take lightly. THE DIVINE The path of yoga gradually reveals to us the underlying nature of reality, in which the "Divine" is universally present in all people, beings and things. But even that explanation takes on Hindu terminology and a Hindu relationship to God. Personally, I have not progressed far enough on the path of yoga to make this statement unequivocally and with integrity. I can understand it in theory, but that is a far cry from the first-hand experience and understanding I prefer before adopting language and teaching into my life. RESPECT The idea behind Namaste is a beautiful one, at least the way it has been generally appropriated in western yoga. A recognition of effort and goodness in others. I prefer to say these things clearly, concisely and in my own language. I gladly offer respect, gratitude, honor and joy when I feel them. I simply use those words. I just finished reading Gregor Maehle's new book Samadhi. In it he describes the eighth and final limb of Ashtanga Yoga.

It is becoming clearer to me that asana (postures) are a small part of yoga. They are certainly not its goal. They serve the vital purposes of bringing health to the body, allowing us to sit for long periods of time in stillness, and strengthening the body to tolerate the intense energetic effects of Kundalini meditation and samadhi. Yoga directs us toward understanding the nature of the mind and of consciousness. The 8 samadhis allow us to experience them firsthand instead of simply thinking about them theoretically. As a yoga teacher in the USA, my teachings are focused around asana. I think this needs to change.

The highest honor we can offer our teachers

Is not to preach what they preach Or to turn their lessons into dogma To be slavishly followed. The highest honor we can offer our teachers Is to think for ourselves; To be critical, to be discerning And to be progressive in thought and action. I regularly teach the 26 posture sequence developed by Bikram. I know the monologue associated with its instruction, but I get further away from it every time I teach.

There are inevitably moments that are the same in every class. Like the Sit-up, where the whole class is meant to do the movement together. These moments require a forceful, rhythmic use of the language that gets repeated several times. The class can simply do what I say as I say it, and the result is that they all do the Sit-up together. But these unison, rhythmic movements are few and far between. I would even argue that they are the least yogic. I want to encourage my students to explore their own experience, to notice their bodies and minds, and to adjust what they need to adjust. I do not want my students to all take the same approach, move their bodies the same way, or even look the same in the postures. Each day is different, and each student is different. Some need to work harder, some need to back off their effort. Some need to bend their spines more, others need to focus on their hips or feet. This is an inevitable challenge of teaching more than 2 or 3 people at the same time. But sticking to a scripted monologue adds a layer of restriction that prevents me from addressing each class, each day and each student appropriately. There is the argument that a scripted monologue allows new teachers to guide their students with more precision and effectiveness than they would be able to otherwise, by using the words of their teacher instead of their own. This is true, though it ends up being detrimental to everyone over the long term. New teachers are often thrust into a leadership role with a poor understanding of the body and the postures, relying too heavily on a script. Also they are prevented from making their own mistakes, enduring their own struggles on the way to developing their own language, tone and pace. New teachers would be better served by studying the mechanics and purpose of each posture and sequence. They should be required to come up with their own language to guide the students based on their own experience of the yoga. That is the only way to keep the tradition alive and prevent it from becoming stagnant and dogmatic. |

This journal honors my ongoing experience with the practice, study and teaching of yoga.

My FavoritesPopular Posts1) Sridaiva Yoga: Good Intention But Imbalanced

2) Understanding Chair Posture 2) Why I Don't Use Sanskrit or Say Namaste 3) The Meaningless Drudgery of Physical Yoga 5) Beyond Bikram: Why This Is a Great Time For Ghosh Yoga Categories

All

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed